THEME 5

_

I want the opportunity to make my situation better.

Some Californians feel trapped in their current situation, leaving them unable to make progress toward their goals.

Participants want the freedom and flexibility to pursue better opportunities within or outside of their communities. However, the weight of joblessness, debt, the high cost of living, and family obligations sometimes keeps them from making progress.

Although government and nonprofit assistance programs in California can help people below or near the poverty line, some Californians still don’t have access to, or know how to access, the help they need. It takes time and patience to locate and apply for the right help.

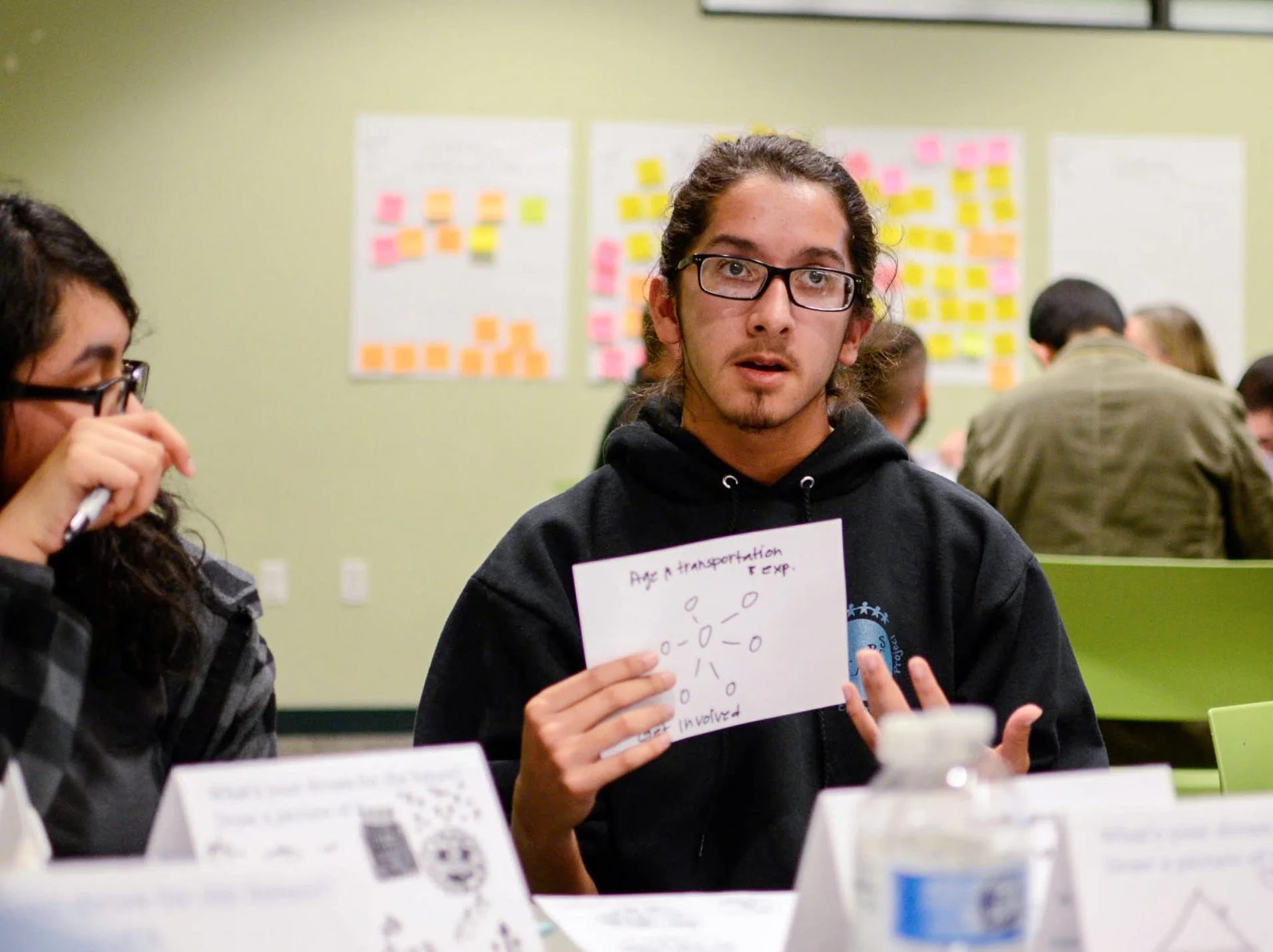

Some participants encounter obstacles to full mobility — from the day-to-day costs of owning a car to the financial and social costs of moving to a new community for a job.

For Californians lacking the right skills and training, low-wage work often turns into a dead end. Some participants feel stuck with little time to find alternate paths. For some of the immigrants we spoke with, not knowing English confines them to their own community, even if the resources that could help them build a better life exist in another area.

Young people from struggling families confront a series of daunting first steps to independence. They face pressure to support themselves without help, give back to their families, and forge a path forward for younger siblings, all at the same time.